Solar Dome Drying House Innovation by IPB University Expert Adopted by Several Police Stations in West Java

The solar dome drying house innovation by Dr Tjahja Muhandri, a lecturer at the Faculty of Engineering and Technology, IPB University, has been adopted by several police stations in West Java, specifically in Subang and Indramayu, for the corn food security program.

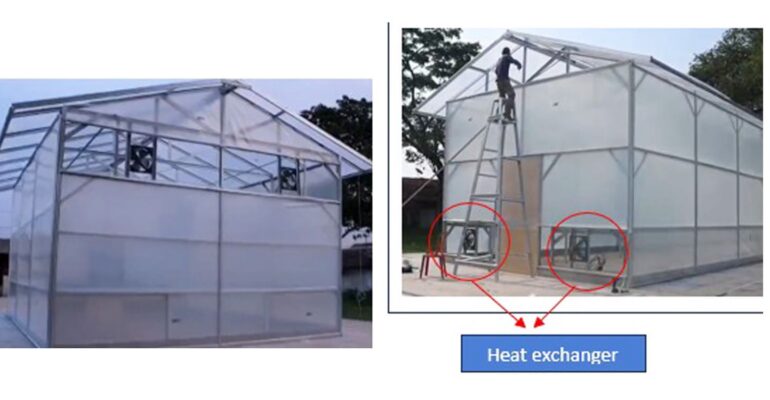

Dr Tjahja explained that the design of the drying house was developed to improve on existing models. This technology is considered more effective than conventional drying houses because it is equipped with a good air flow system and indirect heat transfer heating.

“This drying house design was created by adding a good air flow system and a simple indirect heat transfer heating device. The heater can use any material because the smoke does not enter the drying chamber,” he said when interviewed by the IPB Today editorial team at the IPB Dramaga Campus (1/7).

Drying houses have actually been widely built in the community. However, most of them are ineffective. According to him, many drying houses only consider temperature without paying attention to air circulation. “As a result, many drying houses are not used because the drying process takes too long and the products end up moldy,” he said.

Dr Tjahja added that drying is a process of releasing water vapor from materials that is greatly influenced by the dimensions and properties of the materials, as well as the difference in water vapor pressure between the materials and the environment. Temperature does serve to accelerate evaporation, but without adequate airflow, the drying chamber will become hot and humid, making it difficult for water vapor to escape from the materials.

Dr Tjahja’s drying house design is capable of drying industrial scale raw materials with an effective capacity of around 500 to 1.000 kilograms. Materials that can be dried include grains such as coffee, rice, corn, and soybeans; sliced materials such as ginger, turmeric, cassava, and taro; as well as flour and granules such as palm sugar and cassava flour.

In addition, this drying house is also suitable for horticultural commodities such as chili and onions. This innovation is considered suitable for agricultural businesses. In Indramayu and Subang, this tool has been used to dry corn kernels.

In terms of cost, Dr Tjahja said that the price of building a drying house depends heavily on the materials used. The design can also be modified to suit the conditions and materials available.

In Ponorogo, for example, a drying house made of bamboo and plastic can be built at a cost of around IDR 10–13 million. If using lightweight steel and plastic, the cost ranges from IDR 35–50 million, while the use of high-quality materials can exceed IDR 200 million. “The construction cost is similar to that of a simple greenhouse,” he said.

As a conclusion, Dr Tjahja hopes this innovation can benefit the community. For him, the strength of research lies not only in scientific publications but also in its ability to address real world needs.