Aceh Territorial Dispute in the Spotlight, IPB University Environmental Geography Expert Reminds Us of Small Islands with Similar Fates

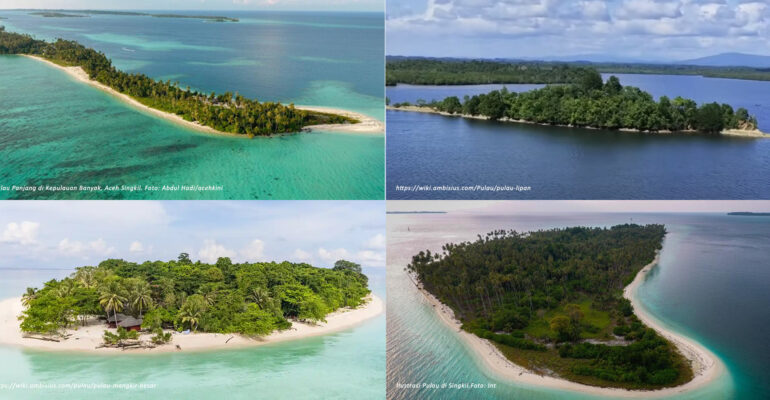

The Minister of Home Affairs’ Decision (Kepmendagri) No. 300.2.2-2138 of 2025, which incorporated four islands belonging to Aceh—Panjang, Mangkir Besar, Mangkir Kecil, and Lipan—into the territory of Tapanuli Tengah, North Sumatra, sparked serious conflict before it was eventually revoked.

Dr Rina Mardiana, an Environmental Geography Expert at IPB University, stated that despite the swift resolution of this case, attention must remain focused on the fate of islands in other regions such as Rempang, Bintan, and Raja Ampat in Papua, which remain in limbo without clarity.

This lecturer at IPB University’s Faculty of Human Ecology assessed that this controversy reflects the weakness of spatial planning and administrative governance in Indonesia. “The Ministry of Home Affairs should have first sought historical documents, not just rely on geographical coordinates. This is highly ahistorical and political,” said Dr Rina.

She referred to various historical evidence, including the 1978 TNI topographic map, the 1988 joint agreement between the North Sumatra and Aceh provincial governments, and Ministry of Home Affairs Decree No. 111/1992 on the Demarcation of the Aceh-North Sumatra Border based on the 1978 map, which states that the four islands are within Aceh’s territory. However, all of this was ignored in the initial decision by the Ministry of Home Affairs.

Dr Rina not only highlighted the administrative process but also emphasized the significant potential of natural resources in the area, particularly the gas reserves in the Andaman Basin. The oil and gas (migas) potential in this region is highly significant and is adjacent to the Singkil Block, which is currently managed by the Aceh Oil and Gas Management Agency (BPMA) in collaboration with Conrad Asia Energy.

“Geologically, this region is part of the same formation as the Andaman oil and gas sources. This means there is the same potential,” explained Dr Rina, who is also a lecturer in the Division of Population, Agrarian, and Political Ecology at the Department of Communication Sciences and Community Development.

However, she continued, the swift resolution of this case raises new questions: why haven’t similar conflicts in Rempang and Raja Ampat received the same attention?

She cited the example of Rempang-Batam, where the community remains confused by the dual leadership between the Mayor of Batam (the regulator) who also serves as the Chief of the Batam Development Agency (BP Batam), which is the investment operator.

“When he arrives, the people ask, ‘Are you our father or the company’s representative? If as mayor, you are our parent; if as BP Batam, you become the extension of investment.’ This dualism is confusing,” criticized Dr Rina.

This confusion is exacerbated by the uncertainty surrounding the land rights of indigenous/local communities and the direction of national strategic projects that are perceived as not benefiting the local community. She explicitly stated that the conflict in Rempang highlights the lack of clarity in land administration and the lack of support for indigenous communities.

In Papua, the situation is even more complex. According to Dr Rina, the relationship between Papua and Jakarta regarding economic benefits is perceived as unfair. Especially if foreign parties exploit the Papuan separatist movement and the government fails to respond seriously, this could threaten national sovereignty.

“If provoked by neighboring countries with vested interests, it could be fatal. The historical wounds in Papua are different. While Aceh’s issue is a referendum, Papua’s issue is territorial separation,” she said.

Dr Rina warned that without proper cadastral administration of small islands and without practices to sustain these small island regions, Indonesia could lose its sovereignty, as in the case of Sipadan-Ligitan.

Small islands are currently targets for investment, both for oil and gas exploration and tourism. However, the government often overlooks the identity and rights of indigenous communities who have lived there for generations.

“Batam, Rempang, and Galang are being positioned as ‘Singapore 2’ and even ‘New Maldives’ in the Thousand Islands. But the government has forgotten to identify the original owners: the indigenous/local communities and the history of their livelihoods, which strengthen the socio-agrarian relationship between humans and the land,” she added.

Recommendations and Solutions

Dr Rina proposed several strategic steps. First, accelerate the Systematic Land Registration (PTSL) of small islands. She emphasized that all areas, especially small islands, must be fully mapped to eliminate any ‘gray zones.’

Second, eliminate dual authority. She emphasized that the government must separate the roles of regulator and investment operator. “Local leaders should not act as extensions of investors,” she stated.

“Third, equal treatment for all regions. The swift resolution for Aceh must set a precedent, not an exception. Regions like Rempang and Papua also deserve fair and swift resolutions, without having to wait for conflicts to escalate,” she said.

Finally, she encouraged collaborative and democratic spatial governance. Dr Rina suggested that every determination of territorial boundaries should involve inclusive dialogue with local communities and be based on historical and socio-cultural studies.

“If only Aceh is handled quickly while Rempang is left to simmer, that’s called biased policy. The Indonesian state needs consistency,” Dr Rina stressed.

According to her, the controversy over the four islands in Aceh should serve as a turning point for the government to improve spatial governance, especially regarding small islands that have long been overlooked.

“Indonesia must demonstrate that regional justice is not just for areas with political power, but a right for all citizens without exception,” she concluded. (IAAS/FMT)